Daydream believers and a Stadium of Light

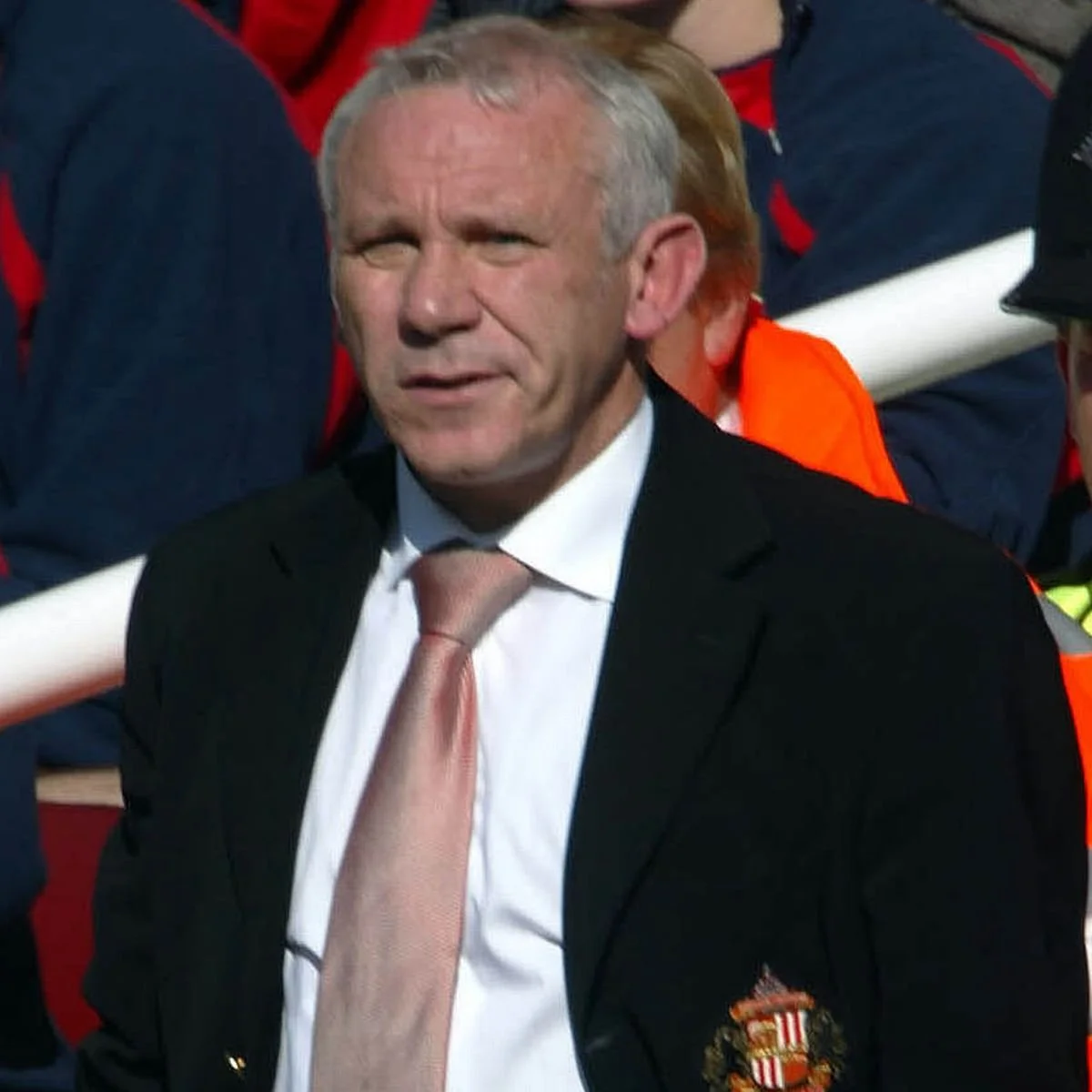

When Peter Reid was appointed Sunderland manager in March 1995 football in the North East was in the ascendency. Kevin Keegan’s entertainers at Newcastle were the most beloved team in the country and on the verge of their glorious but doomed title challenge of 95/96. Middlesbrough had the air of glamour, granted by what would turn out to be a promotion to the Premier League under the management of legendary former England captain Bryan Robson. This would be supplemented by the surreal sight of Brazilian superstar Juninho joining in October of that year. Sunderland in contrast were mired in a second tier relegation battle. Sunderland however had bigger plans as they searched for a gleaming new stadium to take over from the soulful Roker Park. This is the story of a club at a cross roads, caught between ambition and tradition. The story of a team led by a man described by the BBC as a ‘scally messiah’ , who Rob Smyth opined ‘achievements at Sunderland were arguably greater than those of Kevin Keegan at Newcastle.’

Sunderland are a club with a glorious yet distant history. With six titles, they for now sit in joint sixth place, alongside Chelsea and Manchester City in the pantheon of the most League Championships in English football. Three of these successes were to come in the 1890s and the most recent in 1936 running in parallel to the Nazi’s invading the Rhineland. For a period in the 1950s Sunderland were known as the ‘Bank of England’ as a result of their extravagant spending. This however did not bring any further league wins and precipitated disaster. In 1957 they were implicated in scandal after being found guilty of making payments to players in excess of the maximum wage. Sunderland were hit with a heavy fine and the following season were relegated from the top division for the first time in their history. From that onwards Sunderland had alternated between the first and second divisions, and on Reid’s arrival had not since finished in the top half of the highest league. Sunderland were demoted to division two in 1991 and by the time Peter Reid was appointed in 1995 ‘there was mounting concern they would be relegated’ again. Reid was aware of ‘all their problems’ and could see ‘the risk-both to my job prospects and reputation-was great’, but was seduced by Sunderland’s potential. ‘Sunderland were a sleeping giant and someone had to wake them.’ Reid had had a relatively strong start to his managerial career after being groomed for a role in management as assistant to his mentor Howard Kendall at Manchester City. He took over as City manager when Kendall returned to Everton in November 1990. Reid led City to successive 5th place finishes before slipping to 9th in 92/93 and being sacked after a poor start to 93/94 amid criticism of long ball football. Alex Ferguson describes the job Reid did at City as ‘excellent,’ and that he ‘couldn’t believe it when they got rid of him.’ Reid returned to his role as player at Southampton and ‘waited for the phone to ring in the hope a job offer would come his way.’ Reid was desperate to work as a manager but concluded, ‘I seemed to be the only one who saw myself as a manager…I was discovering the hard way that out of work managers can be forgotten quite easily.’ Reid had reflected in his months in the wilderness and felt, ‘I was a bit headstrong, when I would have been better off standing back, taking a deep breath and looking at the bigger picture.’ On arriving at Sunderland however there was not much time to ‘assess the situation’. Sunderland were in freefall having lost six of the past seven games amidst attendances plummeting to 11,000. Reid ‘was offered the job on the basis that ‘initially, I would do it for the last seven games on the understanding that, if I kept them up, we would look at a long-term agreement.’

Reid immediately set to work, ‘there was no opportunity to make new signings and time was against us…I knew that galvanising team spirit would give us the best chance of avoiding the drop.’ As such ‘one of the first things I did was to take the squad out to a restaurant called Bistro Romano armed with £500…we spent £950. I knew then we had a chance of staying up.’ Reid ‘looked to make coming into work as enjoyable as possible.’ Sunderland would lose only one of the final seven games of the season and finished six points above relegation. After keeping Sunderland up Reid was offered his long term deal and promised £1million to spend in the transfer market. Paul Bracewell was brought in on a free transfer and experienced coach Bobby Saxton was added to Reid’s backroom staff. Saxton was to prove a key part of the Reid revolution, Reid himself described him as ‘an old school coach, one of the best I ever worked with, and he got on really well with the players.’ Jeff Brown, presenter of look North on BBC, stated that although seen ‘as a rough and tumble coach,’ doesn’t get the credit he deserves. On promotion in 1999 Kevin Phillips recounts Reid as standing up and stating, ‘none of this would have been possible without one man, Bobby Saxton,’ at which point Saxton ‘got up and gave him a big hug, before walking out of the room crying his eyes out.’ When Reid later enquired about the £1million to spend of transfers, he was told ‘it wasn’t there.’ Reid responded by pulling ‘my car keys out of my pocket and handed them over. “I won’t be needing them”, I said. “I’ll get the train back to Manchester because that’s me finished here.” The board duly relented and Reid was able to sign striker David Kelly. Kelly ‘got injured after a few games and never really hit his stride,’ leaving a vacuum in the striker position which took two seasons to be filled. Indeed Sunderland’s top scorer the following season was Craig Russell with 14 goals, their total of 59 league goals was only better than 3 of the top 16. Reid had embarked on the season thinking ‘we had enough to be safe in midtable.’ Nevertheless ‘the momentum of the previous season continued’ as Sunderland achieved promotion as Champions, ‘built on’ as Reid puts it ‘foundations, with team spirit and hard work proving the cornerstone of everything that followed.’ Shay Given, who joined on loan half way through the season after being told by Reid ‘bring your hair gel…cos we’re on telly at the weekend and you’re starting’, recounts, ‘It’s hard to overstate how positive Reid was…Reidy was all about the craic and he believed, rightly that a strong team off the pitch makes a better team on it.’ Given goes on to state, ‘Reid wanted us to go out together and build up a sense of camaraderie. He wanted us to be like brothers who wanted to fight for each other. He would say, “right lads, we are all meeting in the Chinese at two o’clock on Monday.” You didn’t have any say in the matter.’ Given outlines the importance of Kevin Ball, ‘Ball was Sunderland through and through…He would lead a team talk and wouldn’t hold back. He would stand there and go, ‘let’s get into these fuckers…This is Roker Park and nobody comes here and shows us up.’ Reid concurs describing Ball as ‘really influential.’

Reid himself summarises, ‘of course you need the tactics, you need the analysis and you need the statistics but you also need the human touch because, without it there will be times when relating to players and getting the best out of them can be a problem.’ Niall Quinn describes Sunderland training as ‘a happy place. We love it. Peter Reid keeps the mood light.’ Further describing Reid’s ‘sincerity [and] basic decency,’ and that he was ‘a pleasure to be around all these years…hard working as honest…a friend and a motivator.’ Kevin Phillips concurs ‘I have the utmost respect for Peter Reid. In my eyes he is the ultimate players’ manager, a great motivator and a man you can approach if you have a problem.’ The atmosphere Peter Reid created and the team spirit he cultivated was undoubtedly a major factor in his success at Sunderland.

While on the pitch Sunderland may have been utilising traditional approaches, off the pitch Sunderland were embracing modernity. Following the release of the Taylor report in 1990, Sunderland were obliged to plan to turn the terraced Roker Park into an all seater stadium. Indeed save for Craven Cottage in 2001, Roker Park was the last terraced stadium to be seen in the Premier League. However due to the residential streets encasing the stadium expansion of the famous ground was all but impossible. As such Chairman Bob Murray began looking for a site to build a new stadium on. By 1995 the site of the closed Wearmouth Colliery had been identified as the preferred location. This was approved on 13th November 1995 and completed in time for the 97/98 season. In 1996 Sunderland became only the fourth English club to be floated on the stock market. The 1998 BBC documentary Premier Passions, which followed Sunderland during the 96/97 season, opens narrating a new beginning and depicts a club engulfed by fevered ambition but struggling with its identity amid the changes. Sunderland is described as a ‘City without a cathedral waiting for the new stadium’. ‘Devout fans’ are shown ‘making their pilgrimage’ to watch the construction of what Bob Murray describes as ‘the biggest statement the club has done in 100 years…it says everything about the potential of the club that must be realised…over the next decade there will be success at this club that hasn’t been seen for 40 years’. To go back the 40 years Murray references leads to the scandal of 1957. Fans however were shown stating their reservations, uneasy at the rapid change to traditions but also disappointed as the promised success is slow to materialise. One fan is shown opining Murray is, ‘just looking at the bottom line at the end of the day…Bob Murray is not interested in Sunderland Football Club.’ Another stating, ‘I think he should concentrate on the team rather than floating Sunderland on the stock exchange.’ Some felt alienated by the changes, ‘the basic Joe Public who stands on the terraces…they aren’t really bothered about him…they are going towards corporate facilities.’ Playwrite Tom Kelly and actor Paul Dunn subsequently created a play called ‘I left my heart at Roker Park.’ Sunderland’s groundsman is heard expressing his sadness at the move but concluding, ‘it’s a new era and we need a new stadium to advance to the top which we want. The club is big enough to be at the top.’ For Bob Murray, ‘what we are trying to do is re-establish Sunderland…the stadium is the catalyst for everything…the thing that’ll get us the management, the players, the attractions that is absolutely everything…people who can’t see that are blind.’ Later explaining, ‘this club needs to compete at the highest level.’ As player Paul Stewart stated, ‘there’s more pressure to win as there is more money involved…it’s so much like a business as opposed to a game…and winning is the ultimate prize…winning generates money.’ Taking part in the documentary was itself as Reid notes, ‘ a chance to give the club a mainstream exposure beyond coverage of our matches and to open us up to a new audience.’ For Reid himself, ‘it wasn’t my cup of tea…but it was Bob’s club and he had to make the choice.’ After relegation Murray stated, ‘we need to get to the Premier League and never get relegated again, to win things and be in Europe, that’s where our business needs to go.’ The new ground was named by Murray at a midnight press conference, ‘The Stadium of Light’, representing ‘desire to be in the limelight… like a torch signifies and illuminates the way forward…the name like the stadium will radiate like a beacon to the football world.’ In Premier Passions fans are shown confronting the board criticising the name, calling it a ‘disgrace and a laughing stock.’ Relations with supporters at the opening of the Stadium are described as ‘at an all time low’. One fan stating ‘I’m not buying a season ticket again…we’ve been kicked in the teeth.’ Murray closes the documentary stating, ‘none of us will rest until we are back in the Premiership…we’ll do it until we succeed…we have to make sure Sunderland never ever get relegated again.’ Reid himself explains in his autobiography, ‘Bob deserves a lot of credit for taking us into a new stadium and giving the club the best chance possible of growing and fulfilling it’s massive potential.’

The Sunderland fan base act as a colourful backdrop to everything Sunderland does. Displaying a passion and neurosis fed by the crushing weight of history, the clubs potential and the series of disappointments and let downs of the modern reality. Reid describes the ‘huge passion for football in the area’ but that ‘expectations can rise rapidly the minute things start going well.’ Kevin Phillips recounts the ‘electric atmosphere’ fans provided and that on his first day at the club and that he ‘couldn’t believe it’ that fans had ‘all come to watch the team train.’ He also recalls bad results and being spat at when ‘objects were being chucked…like something you see in those continental matches,’ as well as requiring a police escort as ‘our own fans were waiting to give us a roasting of their own.’ As Niall Quinn states on leaving ‘I’ll miss the raw passion…you can leave the area but you’ll never leave Sunderland, the people, the landscape, the passion.’

The 1996/97 season itself was dogged by injury and the search for a striker. Reid noted that the ‘gulf in class we still needed to bridge was apparent.’ Sunderland were relegated on the final day of the season with a credible 40 points. After completing the signings of goalkeeper Tony Coton and striker Niall Quinn, ‘both got serious injuries which weakened us at both ends of the pitch.’ Reid feels ‘if they had both been able to stay fit, I’ve no doubt that we would have stayed up.’ Premier passions spend much time exploring the search for a striker and Reid’s reluctance to spend money unnecessarily on the wrong players. Reid appears at times uncomfortable with the changing context Sunderland occupied, insisting ‘I’m a football person always will be, I leave the business side to the directors…no added pressure from flotations or financial…’ Reid later stated, as expectations mounted on Reid to make signings, ‘you can’t build a team in two years…I’ve got to do it the way I think is right, with a solid base and go from there…I’ve got my prices and I’ll stick to it...the ones I want haven’t been available…I’m a manger…who has a valuation on a player and I’ll loath to go above it.’ If I ‘buy people I don’t fancy for buying sake…what road will that take me down. I won’t bend for anybody.’ As the documentary progresses Jon Dahl Tomasson is shown around the training ground before the deal collapses and it is later revealed that enquiries were made for Paul Scholes, Andy Cole and Paul Gascoigne. Sunderland’s top scorers that season were Craig Russell and Paul Stewart, who both managed a relatively paltry four league goals. While Reid financial prudence is understandable, it is also evident that largescale transfer expenditure on big names would go against his managerial philosophy. Reid’s success was largely built on a united core of players willing to work hard for each other and boasting enviable team spirit. It is certainly possible to view the inbuilt tension between this approach and the ambitions the club and fanbase held. In the event much of the press surrounding the documentary focused on ‘the furore about the first couple of episodes with some newspapers counting how many times I (Reid) swore to try and build a controversy around the program.’ While his own players acknowledge Reid ‘has a fierce, almost scary temper at times,’ the language and behaviour doesn’t appear particularly scandalous and Reid is adamant ‘no-one who has been in a dressing room…will have been shocked by what they heard.’ Indeed much of Reid’s team talks are imploring his team to ‘keep the fucking football…you can do it…be positive,’ which is in somewhat contrast to the depiction of Reid as a primitive disciplinarian.

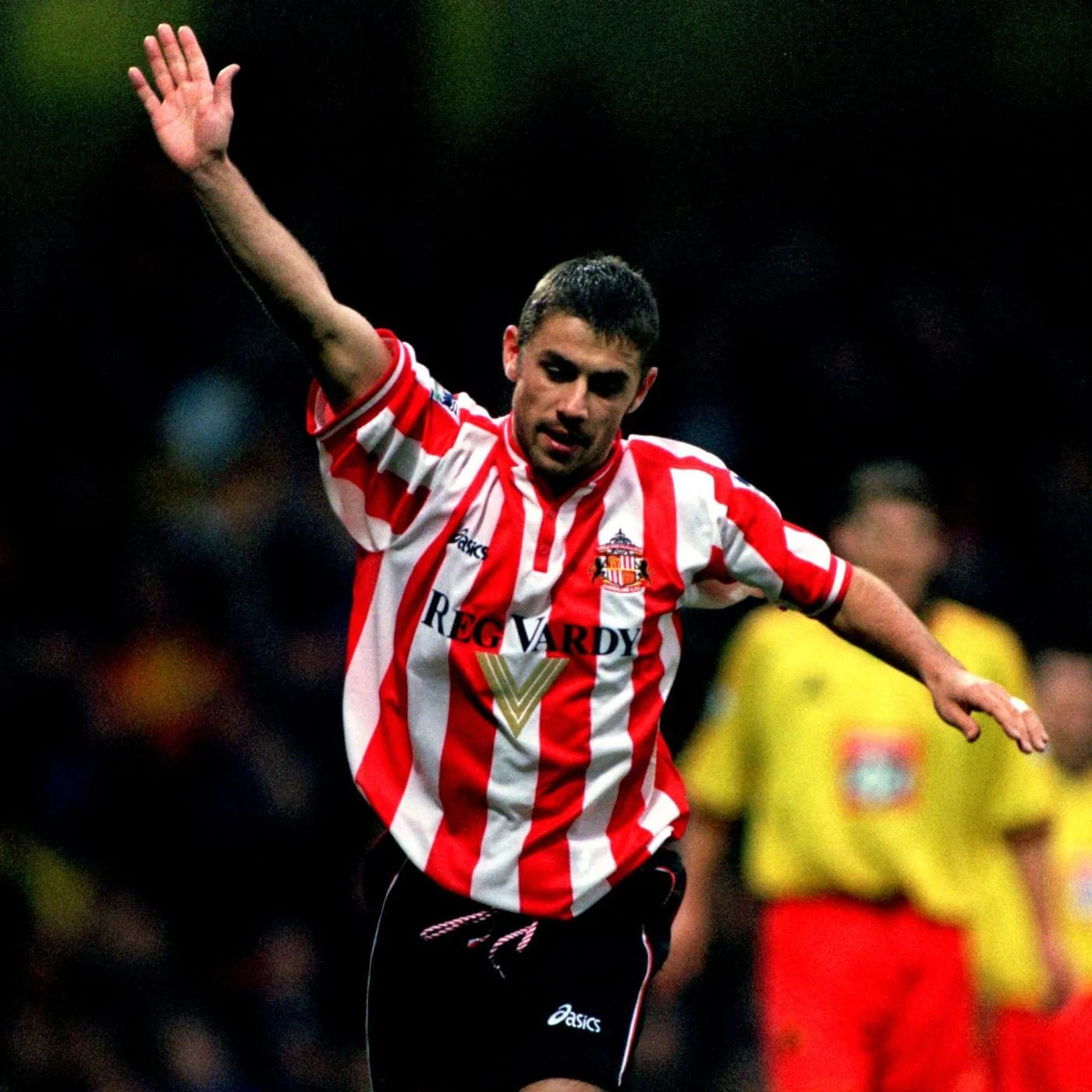

Reid’s approach was to pay spectacular dividends in the coming seasons. While the strike force had been one of Sunderland’s key weaknesses, this situation was to be dramatically reversed. In the summer of 1996, while Newcastle broke the world record transfer fee, spending £15million on Alan Shearer and Middlesbrough parted with £7million to bring in Fabrizio Ravanelli, who had scored in a victorious final for Juventus just months before. Sunderland quietly spent £1.3million on Niall Quinn who was 2 months short of his 30th Birthday. In Quinn’s words, ‘it looked like a journeyman’s move, an end of career shift down the ladder and off into the oblivion of retirement.’ That summer Quinn had been close to signing for Malaysian club Selangor and had even appeared in a friendly for them. Quinn arrived at Sunderland having previously played for Reid at Manchester City, ‘Peter had always believed in me…so when he signed me…after the nightmarish experience in Malaysia it just added to the amount I owed the man…I went to Sunderland determined to make the move something more than a stepping stone to retirement.’ However, seven games into the season, Quinn ‘snapped a cruciate’. Quinn’s career at this point was in tatters as he struggled to recover, ‘my knee wasn’t playing ball…Only Peter Reid believed I’d pull through and play again.’ After missing the remainder of 96/97, four games into the 97/98 season ‘I am desperate not to play but Peter wants me to…I can’t run…my legs are gone…I’m booed off the field. It’s an empty, hollowed out feeling…I’d prefer to quit now.’ Quinn even went as far as to, ‘push the button. Gordon Taylor sent me the requisite forms [for retirement] and a note wishing me well. It seemed all over.’ Quinn was sent to see a surgeon by the club as final throw of the dice, ‘why? I had my retirement forms. I had a job with an Irish newspaper lined up. I was resigned to life after football.’ It was discovered ‘I was suffering from something away from the cruciate…two bones had fused together.’ Quinn quickly had the two bones ‘unstuck.’ Quinn returned to football in a match against Nottingham Forest, ‘Sunderland has been a joy ever since.’ Playing alongside Quinn was an unheralded striker who joined from Watford that summer for £450,000. After biding his time and being patient in his search for a striker, Reid made ‘arguably the best signing I ever made.’ Like Quinn, Phillips had come close to oblivion as a footballer, after being let go by Southampton, Phillips was working in a sunblest factory at age 18 before making his way to Watford via non league. Phillips had scored just 24 goals in professional football when Sunderland signed him. Together with Quinn he would fire Sunderland to the verge of European football. Reid describes the pair thus, ‘as a partnership they were perfect.’ After a poor opening to the 1997/98 season Sunderland suddenly took flight, ‘with Bobby Saxton helping me drill the team and getting them as organised as we could be, we knew that as long as we kept things tight at the back we would have a chance of winning the game with the quality up front.’ Quinn feels that, ‘after a bad start Peter had gambled…Suddenly he threw in Kevin Phillips, Jody Craddock and Darren Holloway. Our wingers Allan Johnston and Nicky Sumerbee came to life. Peter was rewarded with adventurous displays and hatfuls of goals.’ Phillips concurs, ‘the new and improved Sunderland emerged…the gaffer proceeded to drop a few of the more experienced heads…we were alive again. The gaffer had pulled off a masterstroke and the team never looked back.’ In contrast to their promotion season in 95/96, Sunderland would end the season top scorers in the division with Phillips accounting for 31 league goals. Despite their blistering form, Sunderland’s slow start meant they missed out on automatic promotion by one point. Sunderland were thus forced into the playoffs, ‘try getting yourself motivated for that’, as Quinn put it, ‘the play offs are purgatory…the play offs are about beating your own psyche. The third place team as we were, are always in the toughest position.’ After beating Sheffield United in the semi final, Sunderland faced Charlton at Wembley for a place in the Premier League. After a pulsating 4-4 draw ‘a whole season comes down to penalties.’ With Sunderland born Michael Gray missing a decisive penalty, Sunderland were condemned to another season outside the top division. Reid describes the loss as ‘the biggest and most crushing disappointment of my career,’ as he ‘invited’ Michael Gray ‘to my house to try and lift him.’ Bobby Saxton had lightened the mood joking with the stricken Gray, as Quinn states ‘that’s the way teams pull back together.’ Phillips recalls Reid standing up in the dressing room afterwards ‘you’ve done me proud…you’ve all contributed to making this a memorable season and we’ll come back better for it. Next season we’ll give it another go and go one better.’ The mood in the squad remained defiant, Reid outlining that ‘what fired me up was the attitude of the lads. They all vowed to be even better the following season…that spirit was infectious and it went through the club.’

The next campaign as Quinn states, ‘was open season…we cruised the first division.’ It is certainly to Reid’s credit and a testament to the squad he built that Sunderland were able to respond so strongly to the twin crushing blows of relegation and the play off final defeat. The team that season Reid explains, ‘was a very good side. Everyone knew their jobs and we played an exciting brand of football with wide men attacking at every opportunity and looking to get the ball into the box…to put it bluntly most of our opponents couldn’t live with us.’ The squad stayed largely the same, save for the signings of Paul Butler in defence and Thomas Sorensen in goal. Kevin Phillips feels that ‘this season would turn out to be just as much about our squad as our first XI’. Despite injuries nothing could stop Sunderland and the defiant spirit that held the camp together as they finished as champions with a then record 105 points.

Sunderland were finally back and Bob Murray had kept his promise to return to ‘the only place to be…the Premiership.’ That summer again there were few changes. Newcastle native Lee Clark departed to Fulham after wearing a controversial tshirt depicting Sunderland fans as ‘sad mackems’ and Allan Johnston was frozen out after expressing a desire to see out his contract and join Glasgow Rangers on a free transfer. Steve Bould and Stefan Schwarz joined, but as Kevin Phillips stated ‘the lack of activity in the transfer market was causing, not only me but a few of the other lads concern.’ These fears were compounded after Sunderland were soundly beaten 4-0 on the opening day of the season by Chelsea with Phillips stating, ‘I found the pace at which Chelsea knocked the ball around much quicker than what I’d experienced…their players were far more comfortable and competent on the ball.’ From that point onwards Sunderland more than adapted. Jonathan Wilson feels that replacing Johnston with the tucked in Stefan Schwarz on the left benefited the team in adapting to the Premier League by enabling a ‘little bit more solidity in the middle of midfield’ and allowing Michael Gary to overlap from left back. Phillips finished the season as European golden boot winner with 30 goals as Sunderland finished in seventh place and Reid was hailed a ‘Cloughie for the new millennium.’ Sunderland had achieved their first top half finish since the scandal of 1957.

As the 2000/01 season ended Peter Reid had steered Sunderland to a second successive 7th place finish in the top flight. Bob Murray’s ambition of never getting relegated again in a gleaming modern stadium seemed to be coming to fruition. With 18 months however Peter Reid had been sacked and the 2002/03 season ended with Sunderland suffering the fate they had hoped to put behind them as they were relegated. Reid himself feels the club, ‘needed to be more ambitious’ claiming Bob Murray had stated ‘if we finish fourth from bottom every season I’m happy.’ When Sunderland did spend money ‘the foreign market was opening up and it was easy to get your fingers burnt…one of the big strengths of the squad was that it had a British feel to it, especially in the dressing room. Maybe I tried to change that culture too much.’ Reid’s success had certainly been built on an infatiguable team spirt. Niall Quinn would seem to concur that this was lost, ‘we’re not the passionate gutsy team we were a year or two ago…[we] turned into a backbiting rabble.’ Quinn outlined, ‘we stopped calling into pubs on the way home…doesn’t happen anymore in the game…our foreign brethren had to be home for their yoga teacher…the thrill of doing it as a group can help you more than one individual eating pasta for the five days before the next game.’ Perhaps as Jonathan Wilson states, ‘it was a pretty simple approach, 442 get the ball wide into the box…it was right at the end of the period where a manager could be successful with that sort of approach…we were coming to the end of that style of management.’ Reid’s ‘gutsy’ approach built on camaraderie was no longer as effective. The Premier League was opening up to the world and maybe a tactically simple team based around British players who would fight for each other was no longer enough. By attempting to embrace modern football, Sunderland had lost what made them special and they were unable to adapt to new methods sufficiently to keep pace.

When Peter Reid left the club in 2002 Bob Murray was effusive in his praise, ‘Sunderland is totally unrecognisable now to when Peter Reid walked through the door in 1995.’ Peter Reid’s reign has proved to be by far the high point of the club’s time at the Stadium of Light as they now languish in the third tier. With retrospect it is maybe clearer that this was an trick of the light, not the dawning of a bright new era but the final raging against the dying light of the past.