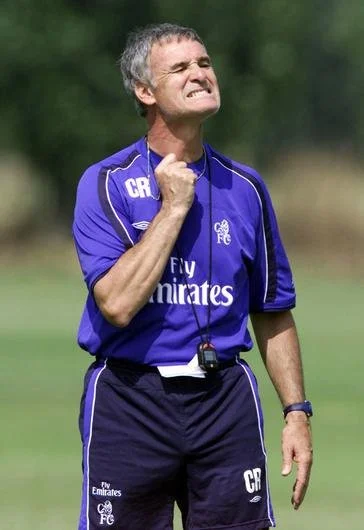

Ranieri at Chelsea: Claudio’s gift to Jose.

Whilst Jose Mourinho was Inter Milan manager between 2008-10, he found himself facing a new yet familiar rival with Claudio Ranieri at Roma. In customary Mourinho fashion he aimed a series of barbs at Ranieri as the two battled for the title, notably stating ‘It is really not my fault if he was considered a loser at Chelsea.’ Jose expanded ‘Ranieri...has the mentality of someone who doesn’t need to win. He is almost 70 years old. He has won a Super Cup and another small trophy, and he is too old to change his mentality.’ Perhaps more than any other of his managerial adversaries, Mourinho’s career is intertwined with the genial Italian. Ranieri was there at his lowest depth as his Leicester City side defeated Mourinho’s Chelsea in 2015 leading to Mourinho’s second sacking at Chelsea and Ranieri sowed the seeds for Mourinho’s greatest dynasty at Chelsea. Perhaps while Jose was needed to add the winning mentality to Chelsea, that ‘was never going to happen with him, ‘it was Ranieri who prepared some of the ingredients that made that dynasty so successful.

As a native Roman Ranieri would have been familiar with the crumbling empire he inherited when he became Chelsea manager in September 2000. While Chelsea had won the FA Cup in May, a cursorily look at the starting 11 for the final reveals the underlying issues. Chelsea lined up with Ed De Goey (aged 33), Melchiot (23), Desailly (31), Le Boeuf (32), Babyaro (21), Deschamps (31), Di Matteo (29), Wise (33), Poyet (32), Zola (33) and Weah (33). As the Chelsea pensioners watched on the team had become a resting place for stars with their best days behind them. Frank Lampard recounts David O’Leary telling him ‘Chelsea…were throwing money at old pros whose hunger for success had long been sated.’ Chelsea had finished 5th the previous season, and whilst the financial problems that dogged the club had not yet become apparent, this would something they would soon have to contend with. Chelsea started the 2000/01 season poorly under manager Gianluca Vialli. Some of the older players had become unhappy with Vialli’s management. Jimmy Floyd Hasselbaink talks of ‘screwed up internal relations…some…still regarded him as their friend and expected him to treat them in the way they had always done…[this] led to the emergence of two factions within the team.’ Furthermore, as John Terry put it ‘we have taken a bit of stick for not brining young players through.’ On Boxing Day 1999 Chelsea had infamously become the first English team to name a starting 11 with no English players.

In this context, appointing a journey man Italian manager new to English football close to his 49th Birthday may have seemed like the continuity candidate. Ranieri’s record however suggested otherwise. Valencia had reached the Champions League final that summer and would go on to repeat that feat in 2000/01. Ranieri had managed Valencia from 1997-1999 and is very much seen as the architect of Valencia’s subsequent success. As Gabriel Marcotti puts it, ‘he left behind a legacy, a philosophy that endured…without those two seasons of Ranieri there would never have been the success achieved under Cuper or Benitez.’. Ranieri encountered an underperforming club mired in mid table and reliant on aging superstars such as Romario who lacked discipline. As Ranieri informed the directors ‘we had a big problem…I told him I was going to promote some of the many gifted youngsters…because they actually follow my instructions.’ Ranieri made these changes that would form the basis of Valencia’s success, whilst taking Valencia to 4th place in la Liga and winning a Copa Del Rey. Ranieri states, ‘they appreciated at Valencia that I had laid the foundations for a new era…I have always regretted not having stayed longer to reap what I had sown.’ Earlier in his career Ranieri had also taken Fiorentina from Serie B in 93/94 to 4th place in Serie A and a Copa Italia triumph. As with Valencia, Ranieri had left a side who would continue to flourish after his departure, finishing 3rd in 98/99. Ranieri had built a reputation as a man who could keep teams competitive whilst building for the future.

Ranieri arrived at Stamford Bridge pledging that ‘big names and big reputations mean nothing to me…I will be treating the youth team players just the same as the reserves and first team stars. They will all be given a chance.’ Ranieri was keen to ‘build the future of the club on a strong English base…a team should reflect the character of the home nation’. Initially Ranieri encountered difficulties in putting in place his ideas. As Carlo Culdicini explains, ‘he really did not speak a word when he arrived.’ Ranieri had used Gustavo Poyet as a translator which became an issue as Ranieri sought to phase older players such as Poyet out of the side. Eventually as Graeme Le Saux remembers Poyet ‘told him he could stick his translating service up his backside’. Ranieri was attempting to bring about a stricter and more professional approach to training. As Mario Melchiot puts it ‘Ranieri from day one wanted to teach us tactics. It was boring but necessary’. Ranieri also, as Hasselbaink notes ‘wanted to impose his own training style right away, which consisted of lots of running exercises and fitness tests.’ Ranieri’s strict fitness coach Roberto Sassi became unpopular. Gianfranco Zola states ‘Sassi…was always serious, demanding, and many did not appreciate that.’ This meant as Hasslebaink described ‘he was really bullied by us’ which culminated in an incident whereby ‘we chased after him planning to rub it [snow] in his face’ and Melchiot ‘really laid him out…I broke his ribs.’ It soon became clear that despite his appearance, as at Valencia Ranieri ‘didn’t tolerate insubordination’ and several key players were to depart. In his biography of Ranieri, Gabriel Marcotti frequently alludes to ‘Good Claudio…the smiling gentlemanly, joke cracker…[and] bad Claudio.’ As Zola describes ‘I can see the dichotomy in him… [there is] the nasty determined one. I think I saw it in him at times.’ Ranieri himself put it ‘the first two years were spent making changes to the team, rejuvenating a squad…It was not easy to start a new cycle and take on the responsibility of having to shed historic players.’ This did not always make Ranieri popular with fans or players who grew tired of his ever-changing line-ups and departure of popular players. Le Saux opined ‘the regime was flawed.’ After Dennis Wise put in a transfer request ‘a portion of the crowd really turned on Ranieri.’ Hasselbaink states ‘he switched back and forth…far too often in my opinion,’ while Le Saux feels ‘the uncertainty didn’t do anyone any good...the situation became incredibly unpredictable and unsettling.’ As Zola explains ‘it took him a while to find the right balance and so he changed things around…It think people forget he was overseeing a massive generational change as well.’ Le Saux notes that Ranieri was ‘getting rid of all the senior players he thought might have been a threat to his authority and who he may have felt had gone past their peak…a new regime was beginning to assert itself.’

In the midst of this turbulent atmosphere Ranieri made one change which would prove transformative to the long-term future of the club. One of Ranieri’s first acts as manager was to watch a young defender in a reserve team match, afterwards he sought John Terry out to tell him ‘I’d get my chance’. Terry was 19 years old and had made six appearances across the previous two Premier League League seasons. He was beginning to have some concerns about Chelsea’s continuous insistence of signing a series of experienced centre backs who appeared to be blocking his route to first team football, telling the press ‘I want to prove they don’t need to buy another big name centre half.’ As Vialli had put it, ‘I suppose all the young players have realised it is going to be difficult to break through.’ There are even reports that Terry was due to be sold to Huddersfield in the summer of 2000. Terry later stated, ‘There did seem to be a lack of opportunities, but I never contemplated leaving the club.’ Terry quickly established himself as a first team regular under Ranieri, making 22 premier league appearances in 2000/01. Far from signing big name defenders, Italian international Christian Panucci departed stating ‘I cannot be angry at Ranieri, however as he put a young player, Terry in ahead of me.’ Even more impressively, Terry was named Chelsea’s fans player of the year and nominated for the PFA young player of the year award. Terry is unequivocal on Ranieri’s influence, ‘for me personally he has been great. He’s played a massive part in my career.’ In Ranieri’s diary of the 03/04 season he tells of a story where Terry presented him his England shirt ‘mounted in a glittering frame’ with the dedication, ‘To Claudio. I will never forget the man who gave me my first chance’. When Ranieri was under pressure following Roman Abramovich’s takeover Terry was almost evangelical in his praise of the Italian, ‘I want him there as manager, 100%...I owe my life to Claudio. I won’t forget the man.’ While Terry’s pathway to the first team seems clear now, it is worth remembering that when Ranieri arrived Chelsea’s central defensive partnership, Marcel Desailly and Frank LeBoeuf regularly lined up together for World and European Champions France. It took admirable courage for Ranieri to not only allow Terry to disrupt this partnership, but to sell LeBoeuf in the summer of 2001. As Terry himself stated ‘maybe I would still be sub if Luca had stayed.’ This courage in reflected in the genuine warmth Terry appears to hold for Ranieri.

Chelsea finished 6th in the 0/01 season before embarking on what Gabriel Marcotti calls, ‘one of Chelsea’s best ever transfer windows’. Key to this transfer window was the signing of Frank Lampard alongside William Gallas, Emmanuel Petit and Boudewijn Zenden. Lampard recounts meeting Ranieri when he had the choice between signing for Leeds or Chelsea that summer. Marcotti outlines that ‘first impressions are Ranieri’s forte’ and it is clear from Lampard’s account that Ranieri played a major part in persuading Lampard to choose Chelsea over a Leeds side, who had after all been Champions League semi-finalists the previous season and finished above Chelsea in the league. Lampard explains how he ‘liked Claudio from the moment I met him…There was an instantaneous mutual respect. I liked the fact he was very blunt’ Ranieri was very specific about his wish to improve Lampard ‘he had watched me play, studied me closely on video…the plan was simple: he wanted to balance my play…by coaching me to be more aware of when to make runs forward.’ Lampard was hugely ‘impressed’ that ‘he wanted me for my energy and potential. Ranieri believed he could harness both and help me to become a better player…I had hardly said a word, but he’d already tapped into my desire to want to improve.’ As Lampard states, ‘With Ranieri I knew exactly where I stood and where he wanted me to be. That was the big difference between him and [Leeds Manager] O’Leary. After that I never gave Leeds another thought.’ Once Lampard signed Ranieri kept his word and began making changes to Lampard’s game that would become a key part of his success. ‘Ranieri had spent a lot of time coaching me about when I should break forward and when I should sit…Ranieri was very passionate about his belief in me…what I learnt was how to react to individual situations, to sense when I might have the best chance of a goal or not…I have Ranieri to thank for that. He saw the potential in me when he bought me from West Ham and made it real by curbing my naïve urge to go forwards regardless.’ Ranieri was so dedicated to improving Lampard ‘the lads took to calling me son of Ranieri and referring to him as my Dad.’ Intriguingly Lampard recounts how this change to his game initiated by Ranieri contrasted with the advice given to him by his Father who had been another huge influence on his career. ‘Dad would be…gesticulating for me to make a forward run…I would look to the bench for instructions…and then catch a glimpse of my Dad telling me to do something completely different…Dad quickly realised he had to take second place to Ranieri.’ Ranieri himself explains the change thus, ‘if he was forever running darting forward, he would never be able to count on the element of surprise.’ Lampard also credits Ranieri and Sassi’s regime in improving his body structure, ‘I had never worked on specifics like that before but Ranieri loved it…seeing how my physique has changed since I’ve been at Chelsea, I realise how beneficial it’s been. The first two years were arduous, but I recognised how much my muscle structure has developed.’ Le Saux notes Ranieri ‘must take some credit for the development of Frank…Frank became a very powerful runner over that first season at the club.’ While Ranieri’s methods were criticised by older players Lampard marvelled at how ‘Ranieri already knew every detail of how he would prepare his players for the season…despite a public perception of someone who would bumble his way through…Ranieri was however very precise when it came to matters concerning the team.’ Le Saux ‘much as I disliked’ the Ranieri regime does concede, ‘I can see how it must have helped an emerging player like Frank Lampard…for ambitious young players like Frank and John Terry, it was an exciting club to be part of’. Two of the most important facets of Lampard’s game are his fitness and his late runs into the box, Ranieri played a fundamental part in honing these strengths. When Frank Lampard joined Chelsea in 2001 aged 23, he had 2 England caps. Graeme Le Saux recalls the reaction when Lampard signed for £11 million, ‘How much? We all spluttered. It seemed like an awful lot.’ Four years later he was recognised by the Ballon d’Or as the second-best player in the world.

While the summer of 2003 when Roman Abramovich took over Chelsea, or summer 2004 when Jose Mourinho arrived are viewed as key turning points in Chelsea’s history, it is perhaps also worth considering the summer of 2002 in a similar light. Chelsea had again finished sixth in the Premier League in 01/02 and had reached the FA Cup final where they were defeated by Arsenal. Ranieri had been in the job approaching 2 years by which time he had in his words ‘rejuvenated the squad’. For both Lampard and Terry, the summer of 2002 was to change their lives and their career. Lampard recalls his fury at ‘not even being on the fucking wait list’ for the 2002 World Cup. ‘When the shock subsided, I got very angry-not with Eriksson, but with myself.’ Lampard describes watching the World Cup and feeling a ‘very public humiliation’ at not making the squad, likening it to ‘being dumped…I went through the same anger, frustration, self-doubt and loathing’. When he returned to pre-season at Chelsea, he ‘just went for it’ and vowed ‘this year I’m going to take the bull by the horns’ and ‘felt a sense of dedication about the season ahead. I converted the frustration of not going to Japan into a burning ambition to succeed.’ Lampard himself states ‘When I look back now, I know without question that that summer was the pivotal period of my life.’ Like Lampard, John Terry had not gone to the World Cup of 2002. Instead of Terry deciding the nations fate in Japan, ‘It was my life in the hands of the jury.’ On the 3rd of January 2002 John Terry had been out in London with teammate Jody Morris and Wimbledon defender Des Byrne. The trio ended up in a private members club where a fight broke out and they were arrested for assaulting a doorman. Terry spent a night in the cells and was bailed before trial. Terry continued to play for Chelsea but was barred from representing England while the case was ongoing. On the 22nd August Terry was found not guilty. Terry explained in a subsequent interview, ‘I had my bag packed all ready for prison…sometimes it takes an experience like this to make you sit up and take notice of things…I had a good think about what I was doing and I’ve changed my lifestyle…I’ve decided In owe it to myself to change things around.’ Terry went on, ‘my career could have been in ruins…This in a strange way is a new beginning for me and I don’t want any opportunities in football that come my way to pass me by.’ The following summer both were in the squad for England’s summer qualifiers and friendlies. By the time Mourinho joined Chelsea, both had been starters in England’s Euro 2004 campaign.

As Lampard and Terry’s career hit key turning points, Chelsea’s financial situation meant Ranieri ‘did not have as much as one pound to spend on any market. Not even the fruit and vegetable market, never mind the transfer market!’. Despite this, buoyed by ‘the new beginning’ for Terry and Lampard Chelsea attacked 2002/2003 with relish and were top of the league in December. Lampard talks that around this time ‘the three core lieutenants and Mourinho’s command got together’, as he built a strong relationship with Eidur Gudjohnsen and John Terry. Ranieri himself made the comparison between ‘John Terry and Frank Lampard like Michael Jordan and Scottie Pippen’ of the Chicago Bulls. Going into the last game of the season Chelsea were in 4th place level on points with Liverpool who they faced at Stamford Bridge. Chelsea were essentially in a play off with Liverpool for the final Champions League place. Chelsea’s financial situation was by this point so dire that players were told by Chief Executive Trevor Birch, ‘In order to ensure Chelsea FC will still exist next season you have to make the Champions League, in short if you fail to beat Liverpool then the club will go out of business.’ In fact, a draw would have been sufficient, but Chelsea were to prevail as 2-1 winners.

After that victory everything changed. In the summer of 2003 Russian Billionaire Roman Abramovich bought Chelsea and instead of ‘wondering whether the club would be able to resist the temptation to sell Jimmy Floyd Hassselbaink and William Gallas’, Ranieri was suddenly managing the richest club in the world. Ranieri quickly demanded of Abramovich ‘tell me straight away,’ if Chelsea wanted a new manager ‘or else you risk wasting your time and money, and I could be wasting my time as well.’ On being assured he would stay Ranieri became taken by the idea that ‘I need two players for every position.’ This led to a huge influx of players which did create some problems. Lampard felt ‘some of the players who arrived were only interested in themselves.’ Hasslebaink was more critical stating ‘bringing in thirteen new players so rapidly is asking for trouble…they all made the step in their own direction and not necessarily to the team’s benefit.’ Hasslebaink noted Ranieri ‘wanted to be friends with everyone’ but ‘signing thirteen players is like signing your own death sentence,’ before concurring with Lampard that some of the new players ‘weren’t so hungry to win anymore.’ Furthermore ‘there was a completely different team on the pitch every time we played.’ Ranieri for his part remained keen to build Chelsea, ‘I wanted young players who would show promise as future champions’ and saw this as ‘a year of building foundations.’ As the season wore on Ranieri became ‘convinced that we had a very special group of players to build on, and that they would begin to bear fruit next season, with or without me.’ This attitude had however begun to frustrate some of the players. Hasselbaink notes ‘Ranieri didn’t seem to expect us to win any competitions…Ranieri kept telling us, we have a new squad, take it easy, the team has to grow first…every one of the players wanted to go for the title…he never put pressure on the squad.’ Lampard agreed that ‘caution was his style. He was keen on improvements by steps…I would often get frustrated…we lacked the experience of what it takes to lead the pack…and that applies to Ranieri as well.’ As the season wore on the spectre of the fabled winner began to loom over Ranieri’s life. In the lead up to the ill fated semi final of the Champions league against Monaco Ranieri explains that ‘it came to my knowledge that…Chelsea had had a meeting with the representatives of Jose Mourinho.’ Ranieri attributes this pressure as a major contributing factor to his substitutions at half time that led to Monaco turning the tie around and ultimately knocking Chelsea out of the competition. ‘I knew full well the blame was principally mine. What is more, I had let myself be affected by anger over the meeting between the club and Mourinho’s agent, and wanting the win as a way of retaliating, proving my point.’

Chelsea went on to finish second that season to Arsenal’s invincibles, soon after the season finished Ranieri was sacked. By now Ranieri was a popular figure at the club, at his last game the crowd spent almost the entire second half chanting his name, ‘I was deeply touched. I would like to have thanked them all in some way at the end of the day, but I really did not know how.’ For much of the season as the pressure grew on Ranieri the clubs emerging leadership base of Terry, Lampard and Gudjohnsen embarked on what Lampard called ‘a bit of a crusade on our behalf for Ranieri.’ John Terry even stating ‘every player in that dressing room is going to try their hardest…[to] make it almost impossible to replace Claudio…Claudio has been great for Chelsea and it wouldn’t hurt for Chelsea to come out and support him.’ Ranieri recognised ‘John Terry and Frank Lampard represent the real future of this team…the problem was simply I would no longer be a part of it all, and this was heart-breaking.’ Ranieri was ‘confident of having sown good seed…of course I would have liked to reap the fruits myself,’ before noting pride ‘at having brought on Lampard and Terry…I will always follow their progress and have a soft spot for them, as they have become a part of me.’

Ranieri and Mourinho in many ways present as complete opposites. Mourinho charismatically ruthless, focused on winning for himself in the present while Ranieri with customary charm building for the next man. These days Mourinho is more conciliatory towards Ranieri. When Ranieri was sacked by Leicester in 2017 after having finally won a league title, Mourinho was strident in his support. ‘From my experience there are two things Claudio needs to know,’ Mourinho said. ‘The first is that nobody can delete history. You cannot go to the laptop and press delete. And I can promise him also that nobody forgets. Leicester fans will always be positive about his time at the club. They will react in a positive way.’ It is possible Mourinho is aware of the debt he owes to Ranieri. When he arrived in 2004 Mourinho inherited a strong spine featuring a burgeoning leadership core of two players who had started for England in the summers European Championship and had been nominated for PFA player of the year. Mourinho came in and informed his players ‘I am a winner and now so are you. We will win things together.’ Within a year they had won the Premier League. As Marcotti notes ‘of Mourinho’s eleven most frequently used players, all but three…were either signed or developed by Ranieri. This was his legacy.’ Despite their differences, together Ranieri and Mourinho built the modern Chelsea. With Lampard now managing Chelsea their legacy endures to this day.

Ben Jones, The Left-sided Problem

-

On this day in 2001, Zinedine Zidane signed for Real Madrid. This transfer is just one reason why the 2001/02 seaso… https://t.co/bI2J6AT97K

-

Little quiz question…who were the last team (and when) to reach a European Cup/Champions League final and not play… https://t.co/4bZlA9KYHH

-

16 years since this game. Not sure there has been a tournament match like it since, two top class teams, playing at… https://t.co/gbpaqAQ8Qj